Missed Appendicitis

Case Objectives

- Appreciate the variable presentations of appendicitis

- List complications of missed appendicitis

- Understand the advantages and disadvantages of CT in diagnosing appendicitis

- Define “anchoring” and “metacognition” and state their impact on missed diagnoses

- List potential strategies to enhance patient safety in the ED

Case & Commentary: Part 1

A 37-year-old woman with no past medical history went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of vomiting and periumbilical abdominal pain for 6 hours. On physical examination, she was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 110/70 and a heart rate of 85. Her abdomen was soft, without rebound or guarding. She was diagnosed with gastroenteritis and discharged with antiemetics. She was told to return for persistent vomiting, pain, or new fever.

Abdominal pain is a common chief complaint in emergency departments, accounting for more than 6% of the approximately 100 million ED visits in the United States each year.(1,2) The most common surgical cause of abdominal pain is appendicitis, affecting 7% of people during their lifetime.(2,3) Of all ED patients with abdominal pain, however, only 1%-3% will have acute appendicitis, many of which will present atypically.(1,2) Consequently, clinicians may become accustomed to ruling out appendicitis rather than ruling it in, eventually resulting in decreased likelihood of making the diagnosis. To combat this effect, clinicians can adopt guidelines (formal or informal) to prompt consideration of highly morbid diagnoses, such as appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, and diabetic ketoacidosis.(4) Although the frequency of misdiagnosis of appendicitis ranges from 20% to 40% in some populations, implementation of a diagnostic guideline was shown to reduce the misdiagnosis rate to about 6% in one study.(5)

Given the difficulty in diagnosing appendicitis, it would be a mistake to assume that lack of objective signs or the presence of atypical historical or laboratory features rules out serious underlying disease. For example, only a minority of patients with appendicitis will present with the classic history of abdominal discomfort migrating from the epigastrium to the periumbilical region on to the right lower quadrant. Although the white blood cell (WBC) count will be elevated in 70%-90% of patients with acute appendicitis, this test is neither sensitive nor specific enough to rule in or exclude the disease.(6,7) The presence of pain in the right lower quadrant, abdominal rigidity, and migration of pain from the periumbilical region to the right lower quadrant increases the likelihood of appendicitis.(7) Although often atypical, the history and physical exam can be helpful in assessing a patient for appendicitis. For example, the presence of vomiting before the onset of pain makes appendicitis unlikely, as does the absence of right lower quadrant pain, guarding, or fever.

Physicians who wait for clear, easily recognizable signs will miss many diagnoses. Gastroenteritis may cause crampy, intermittent pain, or may result in muscular pain from vomiting, but should not cause significant continuous pain. This diagnosis should not be made unless the patient clearly exhibits symptoms of diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, crampy abdominal pain, and/or fever, which did not appear to be true for this patient. The presence of pain should increase suspicion for serious underlying conditions, including appendicitis, even if vomiting is present. If uncertain, the clinician must decide whether imaging or continued inpatient observation is required, or whether the patient is safe to return home. In either circumstance, clear discharge instructions should be provided.

When abdominal tenderness is present, a computed tomography (CT) scan can enhance the diagnostic accuracy of appendicitis. However, if the suspicion for acute appendicitis is high, surgical consultation should not be delayed. Anecdotal but widespread concerns have been voiced about potential overreliance on CT scan by emergency physicians and surgeons. The time, expense, and radiation associated with CT is not warranted when the diagnosis can be reliably made or otherwise excluded. For example, the diagnosis of appendicitis in the man with classic right lower quadrant tenderness and other typical signs and symptoms does not require confirmatory CT scan. However, for women, in whom ovarian pathology can mimic appendicitis, and for men whose diagnosis is less certain, obtaining a CT scan is appropriate.

Although sensitivity of up to 100% has been reported for CT scans of the appendix (6), in typical practice the sensitivity is more likely to be 80%-96%.(8,9) Thus, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of false negative scans. Conversely, the specificity of appendiceal CT is not perfect. A Bayesian approach is needed: widespread use of CT in low-risk patients will lead to significant numbers of false positive test results and unnecessary appendectomies. In some cases, a period of inpatient or outpatient observation is warranted despite the CT report. Patient teaching (including thorough discharge instructions) and good communication are the routes to minimizing error.

The best approach to evaluating an ED patient with abdominal pain is to maintain suspicion for early disease, even disease not yet diagnosable, and instruct the patient accordingly. A nonspecific diagnosis of “abdominal pain” can be appropriately followed by a discussion with the patient surrounding “red flag” signs and symptoms as well as the expected course. If abdominal tenderness is absent and there is no justification for CT scan or extended hospital observation, careful instructions must include warning signs of more serious disease. Then, if the patient returns with appendicitis, the initial encounter cannot be counted as a failure, but as a success.

Case & Commentary: Part 2

The patient presented to her primary care physician’s office 2 days later with complaints of persistent abdominal pain; her vomiting had resolved. Her primary physician called the emergency department to obtain the report. On exam, she was afebrile with normal vital signs. She had a diffusely tender abdomen with some localization around the umbilicus and an unremarkable pelvic examination. A transvaginal ultrasound was scheduled for the following week. The patient was sent home, with instructions to take naproxen for the pain.

Diagnostic assumptions and prior reasoning of others can be carried along, unchallenged when the facts and conclusions of previous assessments are absorbed into subsequent diagnostic reasoning. This cognitive error of “anchoring” is a common source of emergency department error, and error in medical care more generally.(10) In the emergency department, conclusions and assessments of paramedics, nurses, and other physicians initiate assumptions about both acuity and diagnosis. An initial error can be propagated if not reassessed, leading to delayed recognition of serious disease or even mistaken diagnoses. Transitions of care are high-risk points for error, allowing insertion of “pseudo-information,” and enabling “posterior probability error,” in which diagnostic probability assessment is influenced by preexisting diagnoses.(11)

Before final patient discharge, the clinician must stop and think broadly about the case in order to minimize cognitive error. To avoid such errors, expert clinicians apply “metacognition.”(12) The caregivers ask themselves, “Given the same set of facts and circumstances, is there an alternative explanation that may be more accurate? Have all possibilities been taken into account? Are all issues properly addressed?” Applying this “big picture” assessment can prevent error.

Diagnostic error often occurs when patients present atypically.(2) Adverse events correlate with false-negative determinations. The route to improving diagnostic decision-making in ED patients with abdominal pain is to maximize diagnostic sensitivity by careful consideration of the possibility of appendicitis.

Case & Commentary: Part 3

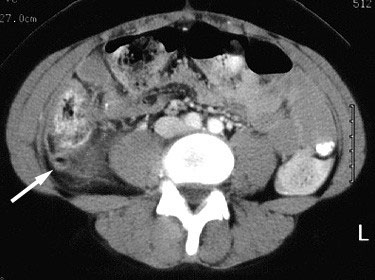

The next day, the patient returned to the ED with persistent pain. She was seen by the same ED attending, who then asked a colleague to evaluate the case. This second ED attending performed a pelvic exam and ordered a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. The CT revealed a perforated appendix (Figure 1). The patient was seen by general surgery and it was decided not to take her to the operating room immediately due to the peritonitis. She was admitted and started on IV antibiotics. Her hospital stay was prolonged due to ileus. On hospital day number #8, her WBC count began to rise. A repeat CT scan revealed an intraabdominal abscess (Figure 2) “the size of an orange.” The patient underwent percutaneous drainage by interventional radiology. On hospital day #13, she was discharged to home with a plan to follow-up for elective appendectomy.

Appendiceal perforation increases the risk of wound infection, abscess formation, sepsis, wound dehiscence, pneumonia, prolonged ileus, heart failure, and renal insufficiency. Perforation leads to longer hospital stays and delayed complications such as bowel obstruction. In women, there is a five-fold increased risk of infertility.(2,13)

In lieu of a guideline to ensure consideration of key diagnoses, clinicians can adopt rules of thumb for when to step back and ask for help from a consultant or, as in the present case, a colleague. Diagnostic decision making is a probabilistic exercise that can never be perfect. Recognizing the potential for cognitive bias from prior evaluation, it was wise and admirable to obtain the input of a colleague on the second visit. Physicians are trained to be solitary clinicians, fully accountable as individuals, but tasked to work as members of a team, without training in teamwork skills. The ability to access a colleague’s expertise is critical at any stage of training or experience.

Case & Commentary: Part 4

Shortly after discharge, the abdominal pain returned. The patient returned to the ED and underwent a repeat CT scan, which revealed a small bowel obstruction. The patient went to the operating room the next day for lysis of adhesions and appendectomy. Eight days later, the patient was discharged home. She has returned to her previous state of health.

Emergency physicians often do not know the outcomes of patients. Experience does not lead to expertise, only feedback does. Implementing ways to increase feedback will enhance quality and may minimize error.(14) Especially in the emergency department, the presence of supportive feedback loops can promote quality and safety.

To enhance safety in the emergency department, a Center for Safety in Emergency Care has been established.(15) This group has formed because of the recognition that the ED is a complex, difficult, and error-prone environment marked by excessive cognitive burden, distractions, interruptions, and time pressure. Identifying optimal practices that maximize safety is an important undertaking. If we are truly going to improve ED safety and quality, we must account for all of these pressures, distractions, and challenges. The safest ED systems include highly trained caregivers, both doctors and nurses, working as a team, utilizing good communication techniques. Interruptions, computer demands, forms, documentation, phone calls, interpersonal conflicts--these all distract from an attentive, thorough, and therapeutic relationship with the patient. This relationship is critical as it forms the foundation of high quality, safe, and satisfactory patient care.

Minimizing misdiagnosis of appendicitis has always been and will remain a challenge, requiring an enlightened system of care as well as informed, expert caregivers.

James G. Adams, MD Professor and Chief, Division of Emergency Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University and Northwestern Memorial Hospital Chicago, Illinois

Faculty Disclosure: Dr. Adams has declared that neither he, nor any immediate member of his family, has a financial arrangement or other relationship with the manufacturers of any commercial products discussed in this continuing medical education activity. In addition, his commentary does not include information regarding investigational or off-label use of pharmaceutical products or medical devices.

References

1. McCaig LF, Ly N. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2000 emergency department summary. Division of Health Care Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number 326, April 22, 2002.

2. Graff L, Russell J, Seashore J, et al. False-negative and false-positive errors in abdominal pain evaluation: failure to diagnose acute appendicitis and unnecessary surgery. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1244-55.[ go to PubMed ]

3. Peltokallio P, Tykka H. Evolution of the age distribution and mortality of acute appendicitis. Arch Surg. 1981;116:153-6.[ go to PubMed ]

4. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical Policy: critical issues for the initial evaluation and management of patients presenting with a chief complaint of nontraumatic acute abdominal pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:406-415.[ go to PubMed ]

5. Naoum JJ, Mileski WJ, Daller JA, et al. The use of abdominal computed tomography scan decreases the frequency of misdiagnosis in cases of suspected acute appendicitis. Am J Surg. 2002;184:587-9.[ go to PubMed ]

6. Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN. Clinical practice. Suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:236-42.[ go to PubMed ]

7. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589-94.[ go to PubMed ]

8. Ege G, Akman H, Sahin A, Bugra D, Kuzucu K. Diagnostic value of unenhanced helical CT in adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Radiology. 2002;75:721-5.[ go to PubMed ]

9. Maluccio MA, Covey AM, Weyant MHJ, Eachempati SR, Hydo LJ, Barie PS. A prospective evaluation of the use of emergency department computed tomography for suspected acute appendicitis. Surg Infect. 2001;2:205-11.[ go to PubMed ]

10. Kuhn GJ. Diagnostic Errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:740-750.[ go to PubMed ]

11. Beach C, Croskerry P, Shapiro M. Profiles in Patient Safety: Emergency care transitions. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:364-367.[ go to PubMed ]

12. Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decision making. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:110-120.[ go to PubMed ]

13. Mueller BA, Daling JR, Moore DE, et al. Appendectomy and the risk of tubal infertility. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1506-8.[ go to PubMed ]

14. Croskerry P. The feedback sanction. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1232-1238.[ go to PubMed ]

15. Wears RL, Croskerry P, Shapiro M, Beach C, Perry S. Center for safety in emergency care: a developing center meant for evaluation and research in patient safety. Top Health Information Management. 2002;23:1-12.

Figures

Figure 1. Perforated Appendix

Figure 2. Intra-abdominal Abscess