Missing the Point—Eye Injury

Sharma R, Brunette DD. Missing the Point—Eye Injury. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2011.

Sharma R, Brunette DD. Missing the Point—Eye Injury. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2011.

The Case

A 31-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) after suffering multiple lacerations during an assault. The patient stated it was unclear what weapon the assailant had used, but she thought it was a sharp blade of some kind. She had two linear lacerations on her right arm that were superficial and did not require suturing.

She also had a 3 cm linear laceration over her right eyelid. She denied any pain in the eye or vision changes. On examination, her pupillary response and ocular movements were intact. The ED provider did not formally check her visual acuity but asked her to close each eye separately and asked her if she noted any change in her vision (which she did not). The ED provider everted the lid (turned it up to see underneath) and the laceration did not appear to extend through the eyelid. He performed a fluorescence examination and did not note any corneal abrasion or evidence of injury to the globe. The eyelid laceration was sutured without complication. An ophthalmologist was not consulted.

The patient presented to a different hospital 10 days later complaining of eye pain. At that time, she reported to providers that her vision had been poor in the right eye since the attack. She was referred to an ophthalmologist and found to have a ruptured globe. She was taken to the operating room for repair and found to have a 4 mm cut in the cornea that extended 7 mm into the sclera (globe of the eye). This laceration was directly beneath the laceration in her eyelid. The defects in the cornea and sclera were repaired, but she had some residual pain and mild visual deficits after the procedure.

The Commentary

Eye complaints account for approximately 2% of all emergency department (ED) visits and comprise 3.5% of all occupational injuries in the United States.(1) All emergency medicine (EM) providers must able to perform an appropriate eye-focused history and physical examination, recognize vision-threatening disorders, and identify cases when an ophthalmologist should be consulted. As this case highlights, a misstep in any of these can lead to potentially serious consequences for patients.

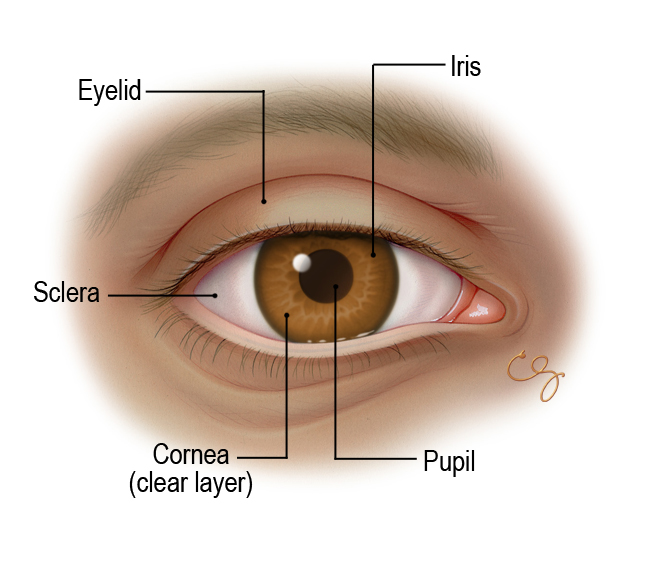

The ED assessment of a patient with an eye-related issue begins with complete ocular history and physical examination (see Figure). Complete history taking includes prior eye history, medical history, nature of any injury, and the presence of photophobia (sensitivity to light), visual loss, diplopia (double vision), pain, or drainage. Each of these questions can yield clues to the underlying diagnosis. Patients who are inebriated or under the influence of drugs may be poor historians, and there should be a high index of suspicion of a serious underlying eye condition. Every EM provider should also be able to perform a basic ocular examination, which includes visual acuity, general inspection, eyelid retraction or eversion, direct ophthalmoscopy (visualization of retina and interior of the eye), afferent pupillary defect testing (special test of reaction to light), visual field testing, extraocular movement testing, tonometry (testing intraocular pressure), and slit lamp examination without and with fluorescein (a dye that can detect injury to the cornea). The use of ocular ultrasound examination by EM physicians is quickly gaining favor as a readily available and easy-to-perform diagnostic test for a variety of ocular conditions such as retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage.(2)

Emergency medicine providers must be able to quickly recognize vision- or eye-threatening diseases and institute prompt treatment or referral. The majority of eye complaints that present to the ED can be treated without the immediate consultation of an ophthalmologist. The Table lists which ocular diseases and injuries require immediate ophthalmologist consultation, which conditions should receive outpatient follow-up with an ophthalmologist without immediate consultation, and which conditions can be managed without ophthalmologist involvement. It is important to note, however, that the EM physician must be able to diagnose, as well as start immediate therapeutic management for all of the conditions listed in the Table. There are several ocular diseases and injuries that require immediate treatment prior to the arrival of an ophthalmologist, such as caustic eye injury (e.g., injury by bleach or cleaning solution) and acute narrow angle glaucoma.

Eye complaints that present to the ED can be broken down into three major categories: the red eye, the painful eye, and vision loss. The causes of these complaints may be traumatic or atraumatic. In cases of trauma, the most serious diagnoses that should be considered and excluded include ruptured globe (as in this case), retrobulbar hemorrhage (bleeding within the eye cavity, behind the eyeball), retinal detachment, and intraocular foreign body. If these conditions are missed and not treated promptly, the patient may suffer permanent visual loss. In atraumatic cases, the most common serious diagnoses that should be considered include acute angle closure glaucoma, corneal ulcer, retinal detachment, temporal arteritis, and ophthalmic herpes infection. These conditions also may result in permanent visual loss if treatment is delayed.

The presented case illustrates the difficulty in assessing patients with periocular and ocular trauma. Up front, history taking is extremely important, and errors in history taking can lead to misdiagnosis. For example, patients frequently present with a sensation of a foreign body in the eye and may not realize that they suffered eye trauma. In such cases, the clue may be that the patient was working near high-speed equipment such as a metal grinder or rotatory cutting tool, and failure to ask about this risk factor could result in the failure to diagnose an intraocular foreign body.

In this case, the patient presented with an eyelid laceration that was caused by a sharp weapon, dramatically increasing the odds of global penetration. Eyelid lacerations in general are high-risk injuries: eyelids are very thin structures that provide minimal protection, and both globe and intracranial injury are therefore common concomitant injuries. There should always be a high index of suspicion of underlying globe injury in patients with small penetrating eyelid lacerations.

Errors in physical examination in patients with ocular complaints can also lead to misdiagnosis. Failure to obtain an accurate visual acuity using a Snellen chart (standard eye chart used in most physician offices) on both eyes independently often results in missed significant ocular injury. Clinicians may be tempted to not formally test visual acuity as it can be difficult to locate the eye chart, hard to move the patient if needed, and the process takes additional time. Consequently, clinicians sometimes simply ask the patient if they notice any blurry vision, as in this case, or only test one of the two eyes. While it is unclear whether the patient above had decreased vision at the initial visit (it is likely that she did), failure to perform and record a true test of visual acuity in both eyes can lead to missed diagnoses. Likewise, skipping or bypassing the other components of a complete ocular examination listed above can result in misdiagnosis. Eyelid retraction or eversion (to examine underneath) is only adequate if the corneal, sclera, and the palpebral conjunctiva have all been visualized. Failure to visualize these structures completely may result in a missed foreign body or laceration. In this case, it was unclear if all these structures were visualized when the provider everted the lid to inspect whether the eyelid laceration had gone completely through. If all structures cannot be visualized due to swelling or other reasons, then the provider should consider imaging studies.

Although intraocular pressure might be lowered in penetrating globe injury, ocular pressure assessment (tonometry) should not be performed, and any maneuvers that potentially increase intraocular pressure must be avoided. If the examination does not reveal globe rupture but there is ongoing suspicion, computed tomography (CT) scanning can be used. However, it has a limited sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing open globe injury (75% and 93%, respectively).(3) Nonetheless, CT scanning can supplement physical examination in diagnosing open globe injury.(3) If a non-opaque, non-metallic foreign body is suspected after CT scanning, MRI may be used.(4) In addition, bedside ocular ultrasound can be used in the diagnosis of open globe injury. Findings include distortion of the architecture, flattening of the globe, and vitreous hemorrhage (bleeding into the fluid inside the eye). Ultrasound examination must be performed with a large amount of gel applied to the closed eyelid (which serves as a cushion for the transducer), and the least possible pressure should be used to obtain images.(5)

Take-Home Points

- Eye complaints are common in the emergency department. Emergency medicine providers must able to perform an appropriate eye-focused history and physical examination, recognize vision-threatening disorders, and identify when an ophthalmologist should be consulted.

- Emergency medicine providers should always do and record an accurate visual acuity examination of each eye independently.

- A normal visual acuity and a normal physical examination do not rule out the possibility of globe penetration.

- Lacerations and wounds involving the eyelid must be carefully evaluated for possible globe and intracranial penetration. When in doubt, radiographic testing (which may include CT scanning, MRI scanning, and/or ocular ultrasound) should be performed.

Rahul Sharma, MD, MBA Assistant Director for Operations Department of Emergency Medicine Assistant Professor and Attending Physician New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center

Douglas Brunette, MD, MPH Assistant Chief of Emergency Medicine for Clinical Affairs Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine University of Minnesota

References

1. Xiang H, Stallones L, Chen G, Smith GA. Work-related eye injuries treated in hospital emergency departments in the US. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:57-62. [go to PubMed]

2. Yoonessi R, Hussain A, Jang TB. Bedside ocular ultrasound for the detection of retinal detachment in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:913-917. [go to PubMed]

3. Joseph DP, Pieramici DJ, Beauchamp NJ Jr. Computed tomography in the diagnosis and prognosis of open-globe injuries. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1899-1906. [go to PubMed]

4. Saeed A, Cassidy L, Malone DE, Beatty S. Plain X-ray and computed tomography of the orbit in cases and suspected cases of intraocular foreign body. Eye (Lond). 2008;22:1373-1377. [go to PubMed]

5. Jehle D, Bouvet S, Braden B, Hendry M, Nagel J, Reidy J. Emergency Ultrasound of the Eye and Orbit. Buffalo, NY: Grover Cleveland Press; 2011. [Available at]

Table

Table. Ocular Disease and Injury: Recommendations for Emergency Department Ophthalmologist Consultation

| IMMEDIATE CONSULTATION WITH OPHTHALMOLOGIST: |

|---|

Trauma |

• Retrobulbar hemorrhage • Severe chemical and thermal burns • Traumatic hyphema • Traumatic iridodialysis • Lens subluxation or dislocation • Scleral (globe) rupture • Traumatic and atraumatic vitreous hemorrhage • Acute retinal injury • Optic nerve injury • Complicated eyelid lacerations, such as lid margins, involvement of canalicular system, levator or canthal tendons, orbital septum, and tissue loss • Conjunctival, scleral, and corneal lacerations • Orbital and intraocular foreign bodies • Posttraumatic corneal ulcers • Retinal tears and detachment |

Infection |

| • Endophthalmitis • Corneal ulcers and infiltrates • Herpes simplex and zoster • Orbital cellulitis |

Glaucoma |

| • Acute narrow angle glaucoma |

Vascular |

| • Central retinal artery ccclusion • Central retinal vein occlusion |

Neuro-Ophthalmology |

| • Neuro-ophthalmic visual loss including all diseases affecting prechiasmal, chiasmal, and postchiasmal tissues • Acute extraocular movement deficit • Acute Horner syndrome • Papilledema |

Miscellaneous |

| • Sympathetic ophthalmia • Posterior vitreous detachment |

| OUTPATIENT FOLLOW UP WITH OPHTHALMOLOGIST: |

Trauma |

| • Uncomplicated orbital wall fractures • Postcorneal foreign body removal • Corneal abrasions if symptoms persist > 24 hours • Uncomplicated traumatic iridocyclitis |

Corneal Disease |

| • Ultraviolet keratitis if symptoms persist > 24 hours • Superficial punctate keratitis |

Miscellaneous |

| • Pterygium and pinguecula • Age-related macular degeneration • Adie's tonic pupil |

| NO OPHTHALMOLOGIST REQUIRED: |

Trauma |

| • Periorbital contusion • Postconjunctival foreign body removal • Subconjunctival hemorrhage • Biologic ocular exposures |

Infection |

| • Uncomplicated conjunctivitis (nongonococcal) • Uncomplicated dacryocystitis |

Anatomic |

| • Hordeolum and chalazion • Blepharitis |

Neuro-Ophthalmology |

| • Pharmacologic mydriasis • Physiologic anisocoria |

Figure

Figure. External Eye. (Illustration © 2011 by Chris Gralapp.)