Procedural Mishap: Learning Curve?

Gibbs VC, Leape L. Procedural Mishap: Learning Curve?. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2003.

Gibbs VC, Leape L. Procedural Mishap: Learning Curve?. PSNet [internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2003.

The Case

A 28-year-old multiparous obese female presented for laparoscopic tubal ligation. The patient had undesired fertility and was sure of her decision for permanent sterilization. She consented to a laparoscopy.

During the procedure, poor visualization and inadequate gas expansion led the team to believe that they had not yet entered the peritoneal cavity. Replacement of the trocar and laparoscope were performed. The anesthesiologist then noted a rapid decrease in the patient’s blood pressure and increasing tachycardia, indicating a possible vascular injury. Conversion to open laparotomy revealed bleeding due to a laceration of the right common iliac artery. Pressure was applied and vascular surgery was consulted. End-to-end anastomosis of the artery was successfully performed, followed by the planned bilateral tubal ligation. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course. Serial Dopplers of distal arterial pulses were normal, and the patient was discharged home in stable condition.

The main operator was a trainee, supervised by a senior attending. The trainee was relatively inexperienced in the procedure. The patient was obese, which added somewhat to the complexity, but nevertheless the procedure was considered routine and the complication unexpected.

The Commentary

Major vascular injury, as occurred in this case, is not a rare complication of laparoscopic surgery. Prospective studies have reported that injury to the bowel or major vessels during laparoscopic procedures occurs in about 3 per 1000 cases.(1,2) Vascular injury to the major vessels is second only to neglected bowel injuries as a cause of death in laparoscopic surgery. Such vascular injuries carry a reported mortality of 6%-11%.(2,3) There is probably a great degree of underreporting of vascular injury. In an anonymous, electronic audience-response survey of 1,958 gynecologists, 4% reported they had injured a major vessel with an insufflation needle or trocar at some time during their career.(4) A major factor in the high rate of injury is that the establishment of a pneumoperitoneum and the insertion of trocars at the beginning of the procedure are usually performed blind. The open Hasson technique can be used, but it has also been associated with bowel and vessel injuries.(2,5)

Major vessel injury usually results from a technical error in the placement of the insufflation needle or the first trocar.(6) The most commonly injured major vessels are the distal aorta and the right common iliac artery (RCIA).(7) This injury pattern occurs because most surgeons are right handed and stand during insertion on the left side of the table. In the anesthetized abdomen, the take off of the RCIA lies only 3-4 cm directly below the umbilicus. With abdominal insufflation, the distance from the anterior abdominal wall and the vessel can be increased to 8-14 cm.

How can this type of injury be prevented? A systems approach to prevention requires searching for underlying causes, or “contributing factors” that led to the injury.(8) Accidents usually result from multiple failures, the end result of a complex chain of events. Such seems to be the case here. From this brief report, three obvious concerns are: training, technique, and equipment design.

At an individual level, competence or adequacy of training is often the first issue raised. This may result in a charged atmosphere when such complications are investigated. In contrast, when departmental or institutional review reveals poor outcomes for all surgeons performing a given procedure, complications are often cast as an expected result—“the learning curve”—that is associated with learning any new procedure. In truth, learning to perform laparoscopy safely is not simple—for trainees today or for practicing surgeons who had to acquire this technique as it became more widespread. Because it is a blind process, safe insertion of the insufflation needle and the trocar requires that the operator have an accurate three-dimensional conceptualization of the spatial relationships between the organs, instruments, and the tissue planes—an acquired cognitive skill. A feel for how much force should be applied during trocar insertion, the proper angle, controlling thrust, and familiarity with the resistance of the distended peritoneum, are learned motor and sensory skills.(2,3)

The challenge of surgical training is to provide experience safely, to enable trainees to transit their learning curves without harming their patients. Laparoscopy is a special case. In open surgery, the visualized field and the close working relationship between the senior surgeon and the trainee permit anticipation and interception of errors. In laparoscopy, however, the supervisor can neither feel the tissue resistance nor control the force of trocar insertion, so the prior experience and motor and cognitive skills of the trainee assume greater significance. It is especially important for the trainee to acquire experience through supervised practice on cadavers, animals, or simulators before operating on patients.(9,10)

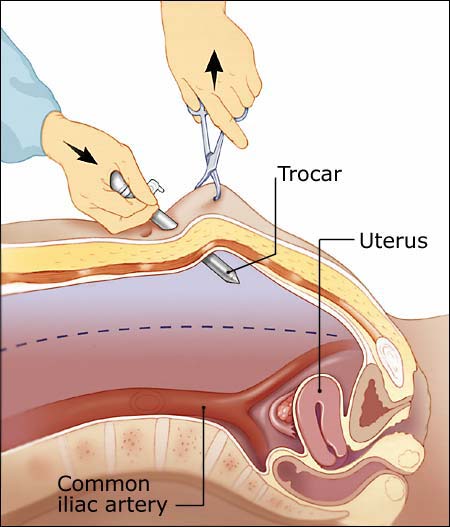

The second category for potential system failure involves technical aspects of the procedure. A common cause of complications for any surgical procedure is failure to adhere to technical protocol. For example, during insertion of the insufflation needle, it is important for the assistant to “tent up” the abdominal wall and to hold the skin tight at the umbilicus so that when the needle is inserted it does not penetrate the bowel or blood vessels. Establishing an adequate pneumoperitoneum prior to inserting the trocar is crucial, both to tense the peritoneum so it can be punctured and to provide safe distance between the trocar tip and major vessels.(Figure)

The most common technical errors of access in laparoscopy are inadequate stabilization of the abdominal wall during needle insertion, inadequate pneumoperitoneum prior to trocar insertion, excessive, misdirected or poorly controlled force directed by the surgeon during insertion, and excessive resistance to trocar insertion by inadequately sized incisions leading to increased subcutaneous tissue resistance.(3) Preventing all of these technical mishaps is more difficult in obese patients.

The severity of the injury in this case suggests it was caused by the trocar. The inability to see adequately after the first trocar insertion implies the peritoneal cavity was not entered, so the second trocar insertion was probably at fault, a conclusion reinforced by the presence of poor gas expansion. Because carbon dioxide gas is rapidly absorbed from the peritoneal cavity, abdominal distension can quickly disappear during difficult or unsuccessful trocar insertion. Thus, after a failed attempt it is often necessary to reinsert the insufflation needle and re-establish the pneumoperitoneum before attempting trocar insertion again.

The third candidate for system failure is the instruments. While a hallowed surgical adage holds that “the poor carpenter blames his tools,” it is nonetheless important to question both the design and the reliability of the devices used. The persistent hazard associated with blind insertion of the trocar has led to continuing search for safer instruments.

Malfunction of equipment is rare. Most injuries involve devices that appear to be functionally normal.(2,3) In a recent review of 408 trocar injuries to major blood vessels reported to the Food and Drug Administration by manufacturers from 1993 through 1996, injuries occurred both with the use of a trocar with a safety shield and the use of a direct view trocar where the trocar and laparoscope are inserted as a unit.(3)

Recently, trocars have been developed with a conical, non-cutting tip and others with a radial expandable tip that pushes through the tissues rather than cutting them. Initial published experience with radial expanding trocars suggests that they may indeed be safer than the cutting tip trocars, as no major vascular injuries have been reported to date.(11)

What are the lessons from this case? Given the limits of present-day technology, how can this complication be avoided? Laparoscopy is a procedure in which attention to technical details is especially important. While these details need not be enumerated here, several generalizations seem appropriate:

- Ensuring stabilization of the abdomen before trocar insertion is essential, through adequate pneumoperitoneum and sufficient anesthetic paralysis, or, if necessary, use of towel clips.

- Accepted procedures must be followed to ensure adequacy of the incision, angle of insertion, the amount of force used, etc.

- If the initial attempt at trocar insertion fails, re-establish pneumoperitoneum before reinserting the trocar.

- Trainees should develop tactile and neuromuscular skills through practice on simulators, cadavers or animals prior to initial human experience.

Laparoscopy is a demanding technique, but one that can be performed safely in a very high percentage of patients if accepted procedures are followed.

Verna C. Gibbs, MD Department of Surgery University of California, San Francisco

Lucian L. Leape, MD Department of Health Policy and Management Harvard School of Public Health

References

1. Leonard F, Lecuru F, Rizk E, et al. Perioperative morbidity of gynecological laparoscopy, a prospective monocenter observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:129-134.[ go to PubMed ]

2. Chandler JG, Corson SL, Way LW. Three spectra of laparoscopic entry access injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:478-491.[ go to PubMed ]

3. Bhoyrul S, Vierra MA, Nezhat CR, Krummel TM, Way LW. Trocar injuries in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:677-683[ go to PubMed ]

4. Feste JR, Winkel CA. Is the standard of care what we think it is? JSLS. 1999;3:331-334.[ go to PubMed ]

5. Hanney RM, Carmalt HL, Merrett N, Tait N. Use of the Hasson cannula producing major vascular injury at laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1238-1240.[ go to PubMed ]

6. Nordestgaard AG, Bodily KC, Osborne RW, Buttorff, JD. Major vascular injuries during laparoscopic procedures. Am J Surg. 1995;169:543-545.[ go to PubMed ]

7. Philips PA, Amaral JF. Abdominal access complications in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:525-536.[ go to PubMed ]

8. Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Chapman EJ, et al. How to investigate and analyze clinical incidents: Clinical Risk Unit and Association of Litigation and Risk Management protocol. BMJ. 2000;320:777-781.[ go to PubMed ]

9. Rogers DA, Elstein AS, Bordage G. Improving continuing medical education for surgical techniques: applying the lessons learned in the first decade of minimal access surgery. Ann Surg. 2001;233:159-166.[ go to PubMed ]

10. Scott DJ, Bergen PC, Rege RV, et al. Laparoscopic training on bench models: better and more cost effective than operating room experience? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:272-283.[ go to PubMed ]

11. Bhoyrul S, Payne J, Steffes B, et al. A randomized prospective study of radially expanding trocars in laparoscopic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:392-397.[ go to PubMed ]

Figure

Figure. A Demonstration of Proper Technique for Trocar Insertion* (Illustration by Chris Gralapp)

* Above the dotted line is safe zone of pneumoperitoneum