Editor's note: Dr. Shah, MD, MPP, is an Assistant Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Delivery Decisions Initiative at Harvard's Ariadne Labs. He is also the founder of the organization Costs of Care. We spoke with him about his insights regarding patient safety in obstetrics, maternal mortality, the importance of dignity, and the overuse of cesarean deliveries.

Dr. Robert Wachter: Was there a case that you recall that made you think about how medicine was all less safe than it should be?

Dr. Neel Shah: I was in medical school during an era where patient safety was very much on everyone's mind. In the way I saw it in the trenches as a clinician, we had relatively narrow conceptions of safety that were mostly about trying to emerge from health care episodes unscathed. Meanwhile, people have goals in receiving health care other than emerging unscathed—women in labor have goals other than emerging unscathed. Yet, the primary metric of our success is maternal mortality. You know, survival is the floor of what women deserve. So the animating impulse was trying to look not just for safety but for dignity, and realizing that dignity is in service of safety and other things that we care about as well.

RW: What do you mean by dignity in that context?

NS: Right now, there are efforts to try to figure out how we measure patient experience with something that matters. Sometimes it seems like what we're looking for is customer satisfaction, and patient experience is not about customer satisfaction. It's about dignity, which is recognizing that people bring values and preferences into their care. Their expertise in their own lived experience is critically important to how we ought to be serving them. Only a woman in labor can tell you how much energy she has to push; she can tell you things that nobody else can. In 2019, the most reliable and available way to know how well a fetus is doing is a mom's subjective sense of how much the infant is moving. No technology replaces that. Yet, in our models of care, dignity is the luxury we tack on after we've attended to your safety; when oftentimes valuing the expertise, values, and preferences of the people we care for is actually a service of safety.

RW: When you think about tackling these issues—whether the broad issue of dignity and respect or a more narrow conceptualization of safety in that we don't harm you in the process of delivering care—how is OB [obstetrics] different than the rest of medicine?

NS: So many things about childbirth are justifiably exceptional. The risk tolerance is incredibly low. Most people are expecting this to be a happy episode. It's one of the only windows in health care delivery where you can influence the long-term well-being of two human beings. Sometimes we think of the well-being of the mom and the infant as being an either/or proposition, when it's actually a false choice. That brings a lot of complexity. But at the end of the day, birth and death are life's only two certainties. Fundamentally, labor and delivery is a physiologic process that challenges a lot of norms of the health care system in bringing a pathology lens to the care and service of people. We're mostly caring for well people, and that's really different from other areas of medicine.

RW: Maybe because of all of that rolled together, you're expecting things will go well, and it strikes me that they go so well the vast majority of the time that one can easily think about problems of complacency. Then, sometimes it goes spectacularly badly. I think about my life as a hospitalist where people are coming in sick with a lot of comorbidities; we often have an expectation that things may not go perfectly. How different does that feel both as a practitioner and also as someone trying to make the system better?

NS: I think what you're keying in on is exactly right, about the difference between taking care of the Medicare population versus the young healthy women I primarily serve. But the other thing is that people can be harmed in health care in two ways: when we do too little too late and when we do too much too soon. And in OB, it's less a complacency problem and more the opposite—99% of American women deliver in environments that are functionally ICUs. The definition of an ICU is the ability to staff one nurse to one patient. And the cardiac ICU does that. So does the labor floor. The cardiac ICU can monitor vital signs in real time with telemetry. So does the labor floor. The cardiac ICU can titrate medicine on a minute-to-minute basis. So do we with almost every patient, with Oxytocin. The only difference between the labor and delivery unit and the cardiac ICU is that our operating rooms are actually attached. So we have the most intense treatment environment of the entire hospital for what are fundamentally the healthiest people, and that's where we've gone wrong.

RW: How did that happen?

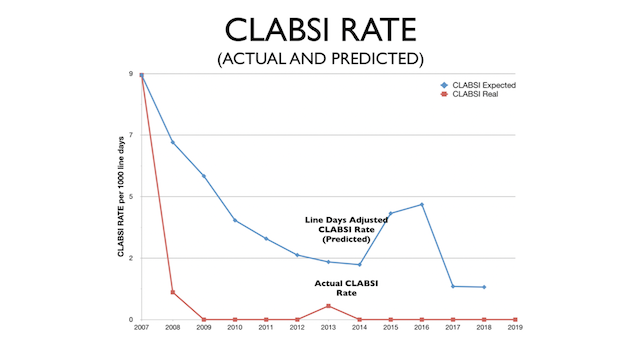

NS: From the 1970s until today, essentially over one to two generations, cesarean deliveries have become the most common major surgery performed on humans, and they've skyrocketed by 500%. No other health care service has increased by so much, and we have not received any material benefit from that rate of rise. Infants are not better off. Moms are actually worse off. In 2019, an American mom is 50% more likely to die in childbirth than her own mother was. One of the underlying issues is that we're doing too much. The odds of experiencing a hemorrhage, sepsis, or organ injury are about three times higher with cesarean delivery than not. We're the only surgeons that cut on the same scar over and over again. If you're a neurosurgeon or a trauma surgeon, and you go back and operate on the place that you operated before, that's a bad day in your work week. But because moms have more than one infant, that's like a Tuesday for me. Every time you do surgery, you're cutting through more and more scar tissue. The first C-section is pretty straightforward. The second or third can be like operating on a melted box of crayons. And the placenta is an organ that only exists in pregnancy. It's a big bag of blood vessels. It gets 25% of everything that the heart pumps. Every once in a while, it gets caught up in that scar tissue, and women bleed to death. That's a condition called placenta accreta, and it's become 1200% more common from the 1970s until now.

RW: So give me your sociopolitical diagnosis of how C-section became overused. How much of it is economics? How much of it is medical malpractice? How much of it is the way we train people or expectations of patients?

NS: There is a lot of conventional wisdom about it. Because it is really stark, when you compare childbirth to other health care services, just how different things look today compared to even 10, 20, or 30 years ago. Many people who are in practice today were around when there was a 5% national C-section rate. Now it's 32%. One, there's a narrative that moms today look different than moms did in the 1970s or 1980s. There's more obesity; moms are older. There's more hypertension, diabetes, in vitro fertilization. There are more multiples. But it turns out that in every demographic category, we see similar increases. If you're a healthy 18-year-old today, your odds of getting a C-section have nearly doubled in many parts of our country, and that has nothing to do with your health. You cannot blame women for these outcomes. Moms are not electively requesting these. Less than a half percent of moms request a C-section off the bat. Medical malpractice doesn't explain it, nor does reimbursement. During eras where reimbursement and medical malpractice policies have been the same, we've continued to see this relentless rise. So there's no straightforward explanation. The best explanation I have is people will procreate whether we give them a safe and dignified way of doing it or not, so it is very easy to normalize the status quo. The status quo in the US right now is that 1 in 3 people get major abdominal surgery to have an infant, and 1 in 10 of their infants goes to the NICU. That's just our norm. There are no alarm bells. Similarly, in other parts of the world where things are much worse, people just normalize how things are.

RW: Given that it sounds like it's more cultural and status quo–based than economic or policy-based or malpractice system or any of that, how do you begin to change it?

NS: One is to recognize that all of us work in a health care delivery systems with enormous complexity. That means we often arrive in these fork-in-the-road moments, where there's a dichotomous choice that a clinician needs to make whether to persist with a woman in labor whose labor is taking much longer than average in the face of a lot of ambiguous data, or to just do the C-section. The fork-in-the-road choice is between the right thing to do and the easy thing to do. One of the biggest opportunities that we have, not only in obstetrics but as a profession, is to figure out how we design systems that make the right thing to do also the easy thing to do.

RW: In your perfect world, what does that look like at that moment of truth? Are we monitoring less, or we don't have these data feeds that are driving these decisions? Are there algorithms that kick in that drive you to a better decision? Or do we tweak the malpractice system? Assuming this cannot happen overnight, but over the course of a decade or two that it often takes to change culture, what does that look like to get to a better place?

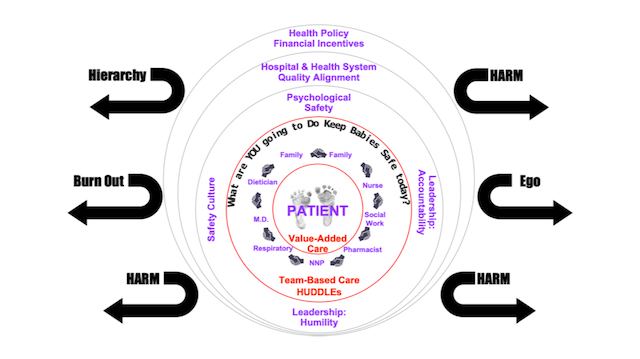

NS: All of the above would be helpful. We're testing something that is very simple, anchored around this notion of dignity. It turns out that for Homo sapiens, childbirth is a team sport. Gorillas deliver their own babies, but we walk upright; we have narrower pelvises. We have dexterity in our hands and the ability to help each other. But the team that comes together to take care of a woman in labor comes together randomly for every woman, every time, everywhere. When we're making these decisions, there will always be uncertainty. No matter what monitoring we pull out of or put back into the system, if a woman has been pushing for 3 hours, then 4 hours, then 5 hours when it's 2:00 AM, there's no objective way of knowing how big an infant's head is until it's out. We need to allow clinicians to exercise their judgment in moments like that. But they ought use all the information that should be available to them in the room, and that information lives in the brain of multiple people. It lives in the brain of the mom, who can tell you things that nobody else can, like how much energy she has to push. It lives in the brain of the nurse, who spends more time at the bedside than anyone else. Every hospital room in the country has a whiteboard in it. They're usually small and usually primarily for the nurse to talk to herself. They're highly variable in content. We made a really big one that sits opposite the mom's head wall, where she can see it. It's simple enough that everyone in the room can understand it. It organizes what the whole team ought to be communicating during every labor assessment, every time. The theory of change is that by integrating the mom's voice into the decision making as a member of the care team and by syncing everybody up when we're in these gray zones, hopefully we're doing it with better, and therefore more accurate, information.

RW: What happens to a mom's preference about vaginal delivery versus C-section, from sitting in a prenatal visit thinking about it calmly to that Hour 4, where she's pushing and nervous and sweaty, and there's a lot of uncertainty around it? Does the patient's preference evolve over time?

NS: It can. Not only can their preference evolve, but what they want their role to be. You don't have a lot of agency when you're in the second stage of labor, which is like running the gauntlet from the minute the cervix is fully dilated to the head passing the narrowest part of the pelvis and coming out. But what's really important is that good teamwork requires psychological safety, which is both the permission and the opportunity to say something when you need to. And you have to develop that well ahead of any problem. That starts in the prenatal clinic and it continues early on in labor, well ahead of when you make a C-section decision. And sometimes the right thing to do is to do a C-section. They are designed to be lifesaving surgeries. But the hardest thing about the C-section problem is that the right answer is not zero.

RW: What is the right number?

NS: There isn't one. It depends on the denominator. It depends on the context. This is another way that C-sections are exceptional. At the hospital level, C-section rates go from 7% to 70% in our country. I'm not aware of another health care service that varies by a full order of magnitude. After accounting for risk, you don't see 10-fold variation anymore. You see 15-fold variation. Which means it's one of the only health care services where after accounting for risk, you see more variation, not less. It means that the biggest risk factor for the most common surgery performed on humans is not a mom's personal preferences or even her medical risk, but which facility she goes to, which door she walks through. Honestly, C-sections are largely a reflection of the capacity of the hospital to support labor, which is a nuanced idea that sometimes can be hard to translate on the front lines when people get very anchored to a specific C-section rate.

RW: Is the variation Hospital A versus Hospital B across the country? Or Hospital A versus Hospital B a mile away from each other? Or Doctor A versus Doctor B within the same hospital?

NS: All of the above. Within the same zip code, your risk of getting a C-section might increase 5-fold statistically depending on which side of town you're on. If you're in an urban concentrated environment—Boston has five academic medical centers in a very small city—and depending on which side of city you're on, the difference in the C-section rate is significant and meaningful. At the physician level, there's also a lot of variation. We found in our own research that it's not just the physician that matters, it's the nurse. Maybe more so. The nurse spends more time at the bedside than anyone else, and we're starting to show that the nurse that gets randomly assigned to you can influence your odds of getting a C-section up to 5-fold.

RW: Wow. Any idea what determines that?

NS: We don't know. If you're a clinician, you're fully read in on the value and influence of nurses. But I often feel like economists and health services researchers are looking through a telescope at a planet that I live on. And they have to make inferences. Nurses don't show up because they don't bill on the inpatient side, so they're not in any administrative claims. As we have started to dig into it, the question you're raising is really the work of the next couple of years. One of our leading theories has to do with presence at the bedside. It's honestly backbreaking work to support a woman in labor and to truly be with them on a regular basis. I'm a surgeon because I may not have the patience for that. But somebody has to do it, whether it's a doula or the RN. In 2019, in a world of central monitoring and the various constraints we have with staffing, it's very hard for nurses to do that. Some nurses spend a lot of time at the bedside, and some spend very little. I think that may be of the key differences.

RW: So much of this is about risk tolerance and predicting the outcomes. You've made clear that a lot of this is quite personal and nuanced and is in the eyes of the participants. I would have thought that all of the variables would be knowable, the size of the head, the contractility of the uterus, the size of the opening, and that some magical AI [artificial intelligence] machine would eventually be able to say this person needs a C-section, this other one does not.

NS: We might get there, but I'm very wary of a blockchain or an AI or a widget of any kind fixing anything in health care without a good understanding of the underlying systems. One thing that has driven up the C-section rate is when we introduce physiologic monitoring of labor. The only thing it does reliably is increase C-section rates because it can tell us information. There is a big difference between accurate information and useful information, or precise information and clinically significant information that we are challenged to sort through. Who knows what the future will bring? But at this particular moment, childbirth remains an artisanal craft. No technology can tell you how big a pelvis is, how big an infant's head is, or how the two are lined up, which is probably more important than anything else, other than a trained pair of hands.

RW: It sounds like you strongly believe that unnecessary C-sections drive a lot of the safety and dignity problems in this area. But if that somehow got better, what would remain as a key patient safety issue in OB?

NS: I'd say C-sections are the thing, because they're so frequently utilized, because there's so much variation. If there's a place with a really high or a really low C-Section rate, it tells you something about the other quality indicators that we care about. Whether it's C-sections or maternal mortality, any one measure is really the canary in the coal mine of a deeper underlying problem in our country in terms of how we support moms. For every one of these maternal deaths, there are tens of thousands of cases of avoidable suffering from chronic illnesses that are undertreated during this period because of care coordination and access issues. There are problems of basic social isolation. Even if you're fairly well connected and wealthy, the period after having an infant is very socially isolating, and it's also very strongly economically disempowering still in our country. If you're one of the 80 million Americans who earns a minimum wage, having an infant means that if you want to work, two-thirds of your income goes to child care. So you can imagine if you're getting POW-level sleep deprivation, trying to earn a living wage, and you're on the margins of illness and wellness or insecurity and security—you're very much at risk of tipping the wrong way.

RW: What have you come to learn about the politics of trying to move the needle on the overall cost of care?

NS: It's something that I'm learning and relearning, and as a country we're learning and relearning. Where every 10 to 15 years, this is happening again. We get to a point where the affordability of health care becomes a kitchen table issue for people. One of the challenges within the profession is figuring out how we talk sensibly about cost in ways that maintain trust with people we care for. When I first started this work, there was so much concern within the profession that patients would think we were skimping on them by addressing costs head-on—it was really hard to get traction. Now we're at a point where our inability to have these conversations is eroding the trust those we serve have in us. If you have a high deductible with $5000 to $8000 out of pocket, if you're pregnant you're guaranteed to blow the entire thing. If you come in for a prenatal visit and I order a battery of prenatal tests that you don't understand, they all get itemized on a bill that's all coming out of pocket, and that's eroding trust in the profession. One of our biggest opportunities now is to take control of that.

RW: How do you come up with a system where you can have that meaningful level of engagement? I look at the 15-minute clinic visit, and the idea that the physician will somehow be able to explain risks, benefits, costs—assuming that he or she knows what they are and often they don't—in that visit space where a patient can actually understand them and make a reasoned decision seems like a fantasy world.

NS: I do have an expectation of us as clinicians with a high bar, where if we're meant in our rising generation of clinicians to wrap our minds around genomics, we can wrap our minds around this too. We should take it on as part of our responsibility to at least understand where the resources are around us; either learn the information you need to learn or send people to the place you need to send them to. Health care is a team sport. It's not all about the clinician and the patient in a closed-door meeting. Right now we have a workflow around clinical care. The flow around patients' experience of that care is decoupled from what we do clinically. The third workflow in the background is around the finances, and there's no effort to coordinate it. For a prenatal test, the patient experiences the blood leaving their vein and that's the end of their experience. Meanwhile, I'm read in on the 15 tests I'm getting, everything from rubella immunity to their blood type. That blood goes through a different workflow. It gets spun in a centrifuge. A bunch of things happen; then on the billing side, another process generates an itemized bill someone will get in the mail a month later. The opportunity to try to think up some of these processes is so tremendous and just seems like low-hanging fruit to me.

RW: Anything else you want to talk about?

NS: I'm concerned that all of the national conversation about maternal mortality might be terrifying people. And there's a public image of what maternal mortality is that may not be fully accurate. A lot of people are imagining going into a hospital, being in labor, and then there being an acute event like a hemorrhage leading to a death. While that does happen, it's exceedingly rare. Maternal mortality in general is exceeding rare. The majority of it actually isn't during the childbirth episode, it's in the period before and afterward, particularly in the period afterward. A lot of patient safety and quality improvement work is like this where it's not just about the systems and the four walls of the hospital that are meant to keep us safe. It's equally about that the systems in the communities where we live our lives are meant to ensure that we're supported.

RW: All of this raises the jumbo jet question of some level of scaring people is probably necessary to move the needle on anything hard, yet you also don't particularly want to scare people unduly. I can imagine women coming in for labor now and being terrified in a way they might not have been until this conversation was more out there.

NS: That's exactly right. But we've done that now. We've scared people and got everyone's attention. Now, we need to focus on solutions and moving it ahead.