Inadvertent Castration

The Case

An 83-year-old man presented with a left groin mass, "which had been there for years" but had recently increased in size. The patient described persistent aching in his left scrotal area, with no identifiable exacerbating or alleviating factors. He noted no change in bowel or bladder habits and reported taking a stool softener. No history was elicited or offered regarding prior genital surgery. Physical examination showed a 20-centimeter left groin mass with some superficial skin ulcerations. The mass was non-tender and was not reducible. The right groin and scrotum were unremarkable.

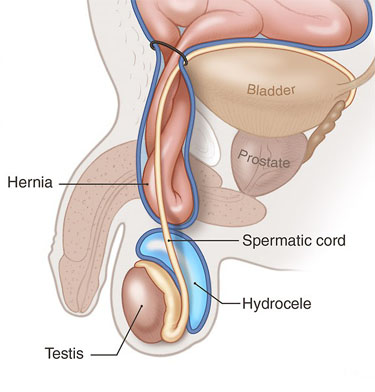

The patient underwent surgery with a preoperative diagnosis of direct left inguinal hernia versus left hydrocele. Although preoperative ultrasound might have allowed this differentiation, it was not performed. Exploration of the left groin revealed a relatively small direct hernia and large left-sided hydrocele (Figure). The planned repair of the direct hernia was carried out, but an intra-operative decision was made to perform complete excision of the hydrocele, spermatic cord, and testicle on the left. The operation was completed without complication.

In the recovery room, the surgeon discussed the changes to the planned procedure with the patient's wife, who informed the surgeon that the patient's right testicle had been removed after a traumatic injury many years earlier. In subsequent discussions with both the patient and his wife about hormonal replacement, the patient revealed that he had not been sexually active for several years. The patient was informed of the benefits of hormonal replacement—on energy level, muscle mass, and bone density—regardless of sexual activity. He elected to receive periodic, intramuscularly injected testosterone.

The Commentary

Adverse events occur during 3%-39% of all surgical admissions, with the operating room being the most common site for errors in care.(1-3) The extent to which faulty communication or planning contributes to this unacceptably high rate of medical injury remains poorly studied.

Several patient safety issues are raised by this case, in which an elderly man with a scrotal mass suffered a medical injury when his only remaining testicle was removed to (inappropriately) treat a hydrocele, resulting in iatrogenic castration. However, without a dispassionate human factors oriented investigation, it is hard to say what really happened. Following a catastrophic accident, a faulty "first story" often emerges that blames the 'sharp end' worker for a failure in vigilance after only a cursory review of the facts.(4) Perhaps just as horrifying as the injury in this case is the reality that workers in the surgical domain commonly avoid similar occurrences by only the narrowest of margins.

Accident Investigation

The case description contains insufficient information to identify the specific safety barriers breached. We do not know the exact setting for the medical injury—urban or rural, community practice or academia, group or solo surgeon—all factors that greatly influence how surgical care is delivered. Likewise, it would be helpful to have information about the extent to which the operating surgeon was involved in the preoperative evaluation process, the availability of consultants, or the intra-operative findings that led the operating surgeon to suspect malignancy as the etiology for the resected mass (which is why I suspect he performed the much larger-than-planned resection). We know nothing of this surgeon's training, the time of day the injury occurred, or pertinent environmental data.

Answers to these questions should be considered essential to medical accident investigation. After sentinel events occur, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) mandates use of varying tools for root-cause analysis, and the Department of Veterans' Affairs (VA) hospitals widely use such tools to investigate accidents and near misses.(5,6) However, such tools are rarely, if ever, used to investigate intra-operative occurrences that don't rise to the level of "sentinel event."

Decision Support

From my reading of the case description, I've inferred that the orchiectomy was probably performed by a general surgeon, apparently without urologic consultation. This procedure may have occurred in a hospital where an urologist was not immediately available, a situation common in smaller community hospitals, and one that cannot be solved by inserting subspecialty consultants in every hospital. In the face of this reality, clinicians and investigators at several universities (and NASA) envision opportunities for multi-media telemedicine, which will allow rural hospitals (or even long-distance space missions) to obtain remote consultation.(7) If my suspicion is correct and this surgeon believed that the mass was potentially a testicular malignancy or did not know how to definitively exclude the possibility of hydrocele, such remote consultation, were it available on-demand in the OR, may have enabled him to acquire the opinion of an expert urologist and subsequently perform drainage or excision of this patient's hydrocele rather than orchiectomy.

Wrong-site Surgery and Other Cognitive Errors

In this case, the surgeon almost certainly never considered the possibility of absence of the contralateral testicle. In this regard, this misalignment of the stars links this case and many other common intra-operative adverse events involving wrong-site surgery.(8,9) This patient had his testicle surgically removed, but similar disasters have occurred in situations involving patients' only remaining kidneys, adrenal glands, or parathyroids. Moreover, similar cognitive errors—failing to systematically rule out unusual but critical issues before plowing forward with a planned procedure or therapy—lead clinicians to fail to recognize and act upon critical patient-specific factors such as drug allergies, potential medication interactions, and religious preferences, as well as how such factors interact with comorbid illnesses.

Similar to other fast-paced, high-risk endeavors, most clinicians committing cognitive errors would take appropriate action had they accurately comprehended the situation—a state generally known as "situation awareness."(10) In medical accidents, gaps in situation awareness and experience, rather than lack of medical knowledge, are often to blame.(11) Combating cognitive errors and supporting situation awareness requires procedures and systems that recognize the frailties of normal human cognition. When complex, multi-step tasks are performed in any high-risk arena, the use of memory aids, checklists, and other fault-tolerant practices, such as placing mission-critical data (eg, the history and physical, operative plan, and diagrams) in the environment, is recommended.

Team Building

The prevailing model for surgical teams tends to designate the surgeon as 'supreme commander,' with sole responsibility for the safe functioning of the team, with some indirect monitoring and occasional modification by the anesthesiologist.(12) Roles of other participants are largely based on experience and familiarity, with numerous critical, yet often unspoken, rules. In this anachronistic model, the non-surgeon physician, resident, nurse, and technician team members are subordinate, with extremely limited capability to crosscheck mission-critical facts or stop the procedure if something goes awry. Unfortunately, another common feature is an even more subordinate level for the patient, who is often expected to behave somewhat like inanimate cargo, even before he or she is anesthetized. Simple strategies emerging from human-factors research, such as pre-operative "pauses" or team-briefings, have the capacity to efficiently orient team members to the task at hand and enable them to "speak up" or challenge something that seems to fall outside standard of care by suggesting alternative courses of action.(13)

An absence of a pre-procedure team meeting, along with the low likelihood that the surgeon or other team members ever participated in simulator training, may have contributed to the safety breakdown that led to this patient's castration. A direct link between such practices and enhanced safety does not yet exist, but indirect evidence supports the common-sense notion that these practices could bolster medical safety. Mandatory team briefings, with invitations by the team leader for participants to step back and speak up if they perceive a gap in safety, are simple, non-resource-consuming interventions that harness the abilities of operating room personnel to help surgeons protect patients.

Prevention of similar events may depend on our ability to adopt more effective human-factors-oriented approaches in accident investigations and Morbidity and Mortality (M & M) conferences, and to explore the potential benefits of adding team building to the list of mandatory competencies for practicing surgeons.

J. Forrest Calland, MD Resident in Surgery Research Fellow and Co-Founder, Surgical Technology and Safety Laboratory University of Virginia Health System

References

1. Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Zinner MJ, Brennan TA. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999;126:66-75.[ go to PubMed ]

2. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370-6.[ go to PubMed ]

3. Andrews LB, Stocking C, Krizek T, et al. An alternative strategy for studying adverse events in medical care. Lancet. 1997;349:309-13.[ go to PubMed ]

4. Cook RI, Woods DD, Miller C. A tale of two stories: contrasting views of patient safety. National Patient Safety Foundation Web site. Available at: [ go to related site ]. Accessed November 3, 2003.

5. Wald H, Shojania KG. Incident reporting and root cause analysis. In: Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001: 41-56. AHRQ publication 01-E058. Evidence report/technology assessment. no. 43. [ go to related site ]; [ go to related site ]

6. Bagian JP, Gosbee J, Lee CZ, Williams L, McKnight SD, Mannos DM. The Veterans Affairs root cause analysis system in action. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28:531-45.[ go to PubMed ]

7. Eadie LH, Seifalian AM, Davidson BR. Telemedicine in surgery. Br J Surg. 2003;90:647-58.[ go to PubMed ]

8. Wald H, Shojania KG. Strategies to avoid wrong-site surgery. In: Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001: 494-500. AHRQ publication 01-E058. Evidence report/technology assessment. no. 43. [ go to related site ]

9. Vincent C. The other side. AHRQ WebM&M [serial online]. October 2003. Available at: [ go to commentary ]. Accessed December 5, 2003.

10. Baumann MR, Sniezek JA, Buerkle CA. Self-evaluation, stress, and performance: a model of decision making under acute stress. In Salas E, Klein G, eds. Linking expertise and naturalistic decision making. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001:139-58.

11. Gawande AA, Zinner MJ, Studdert DM, Brennan TA. Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery. 2003;133:614-21.[ go to PubMed ]

12. Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2000;320:745-49.[ go to PubMed ]

13. Rouse WB, Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E. The role of mental models in team performance in complex systems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 1992;22:1296-1308. [ go to related site ]

Figure

Figure. Anatomy of the Groin. (Illustration by Chris Gralapp)