Around the Block

The Case

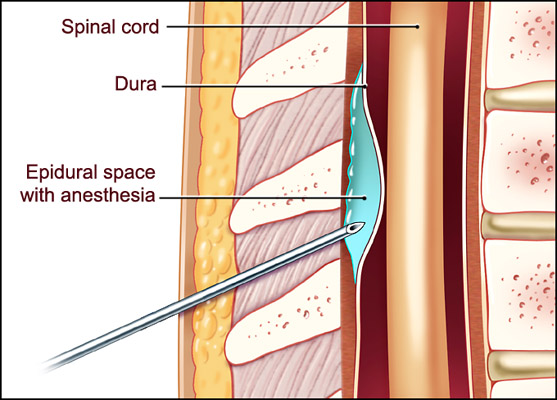

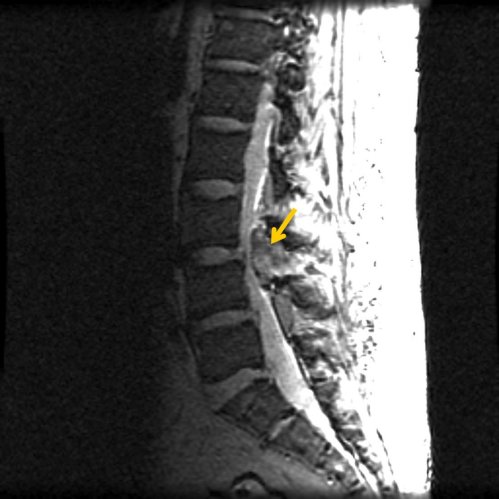

A 77-year-old woman with multiple medical problems was admitted to the hospital for an elective knee replacement. The orthopedic surgeon, recognizing the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), prescribed enoxaparin (Lovenox) for DVT prophylaxis at the time of admission. The anesthesiologist felt that an epidural anesthetic would be safer than general anesthesia in this patient, and placed an epidural catheter to administer the anesthetic (Figure 1). The surgery went well, but soon after surgery the patient developed new onset lower extremity weakness. A "stat" MRI scan revealed a spinal hematoma (Figure 2). Despite prompt recognition, the patient was permanently paralyzed from the waist down.

A retrospective analysis of the case revealed that the admission order form included the statement "Lovenox is not recommended in patients with an epidural," located right next to the check box used to order enoxaparin. A nurse and pharmacist had countersigned the signature block next to this warning.

The Commentary

In this case, a patient received low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) around the time of epidural anesthesia, despite the well described risk of spinal hematoma in neuraxial anesthesia. This case and its catastrophic outcome raise many questions. For instance, should this patient have received pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis at all? Given the risk of spinal hematoma, why use epidural anesthesia? And, perhaps most importantly, how did this series of events occur despite the presence of the warning on the admission form?

Heparin therapy is increasingly utilized in the inpatient setting to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. As DVT prevention is one of the top safety priorities of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), many institutions have developed guidelines for the use of pharmacologic anticoagulation in high-risk patients. Orthopedic surgery patients are a special focus of most guidelines, since such patients are at extremely high risk (40%-60% risk of thrombosis in the first 1-2 weeks after surgery) of postoperative venous thromboembolism.(1) The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends pharmacologic prophylaxis with LMWH, fondaparinux, or warfarin for patients undergoing total knee replacement. Although intermittent pneumatic compression devices are an alternative to pharmacologic prophylaxis, poor compliance and improper use of these devices limit their utility in real practice.

Neuraxial blockade, a method of regional analgesia or anesthesia that targets the centroneuroaxis (eg, spinal anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, or continuous epidural analgesia), carries certain advantages. Compared with parenteral opioids, epidural analgesia results in better postoperative pain control.(2) Compared with general anesthesia, neuraxial methods result in fewer postoperative cardiac events, pulmonary complications, and cases of venous thromboembolism.(3-5) Postoperative epidural anesthesia also facilitates rehabilitation and shortens hospital stay.(6)

Spinal hematoma complicating neuraxial blockade is rare. The incidence of neurologic dysfunction resulting from such hemorrhagic complications is approximately 1 in 150,000 for epidural and 1 in 220,000 for spinal anesthetics.(7) Even though the complication is unusual, the consequences—often spinal cord ischemia and subsequent paralysis—are so severe that it has received considerable attention. Risk factors include traumatic needle placement, repeated insertion attempts, and concomitant use with anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. Most cases are associated with hemostatic abnormalities, either patient-related or iatrogenic.(8) In 1997, the FDA released a public health advisory (9) after more than 30 patients developed spinal hematoma after receiving LMWH around the time of neuraxial anesthesia, most commonly for orthopedic surgery. Although cases also have been reported with unfractionated heparin, the complication is much less common, for reasons that are not well understood. In 9 published series of more than 9,000 cases of patients receiving neuraxial anesthesia and prophylactic doses of unfractionated heparin, no complications were reported.(10)

In response to this serious patient safety issue, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) convened a Consensus Conference on neuraxial anesthesia and anticoagulation in April 2002.(11) The guidelines that came out of this conference encourage clinicians to weigh the risks and benefits of using pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis or full-dose anticoagulation treatment in patients receiving neuraxial anesthesia. For such patients, the guidelines recommend needle or catheter placement during normal hemostasis, administration of the lowest efficacious dose of anticoagulant medication, and close monitoring of the level of anticoagulation and patient's neurologic status during the period of neuraxial catheterization and after catheter removal. The Table outlines recommended approaches for the use of prophylactic LMWH in patients undergoing neuraxial anesthesia. The risk of perispinal hematoma can be minimized by respecting the minimum time interval required between dosing of heparin and removal or insertion of the epidural needle or catheter.(11,12)

Without all the details, we can only postulate what went wrong in this case. The hospital had taken a strong stance against the use of LMWH in patients receiving neuraxial anesthesia —the warning was preprinted on the order sheet. However, this safeguard failed. The use of LMWH in this setting is not contraindicated, but concomitant use does require strict adherence to the guidelines mentioned above. Most likely, the LMWH was either given too close to the time of catheter insertion preoperatively, or it was given too soon postoperatively.

If given preoperatively, we are left to wonder whether the anesthesiologist realized that it was "on board" when he inserted the epidural catheter. If he did not, how could this happen? Perhaps the medication was not charted correctly or the anesthesiologist could not find the chart. Or perhaps, because it is not standard for patients to receive preoperative LMWH, the anesthesiologist did not look for this. Conversely, the orthopedic surgeon may not have known the anesthesiologist was planning on neuraxial anesthesia when she prescribed the Lovenox. If the LMWH was given too soon postoperatively, this could have stemmed from incomplete sign out from the OR to the PACU regarding type of anesthesia, or perhaps the providers simply did not know about this contraindication.

Three approaches could help prevent this error in the future: educational campaigns, forcing functions, and standard procedures. Education might involve training for all providers, with particular emphasis on the timing of LMWH therapy and the need for communication about anesthesia type. Forcing functions might include a pharmacy-triggered warning when neuraxial anesthesia is ordered in a patient who has a previous order for LMWH, or a checklist for anesthesiologist review of all medications received in the prior 24 hours performed before anesthesia is administered. At UCSF Medical Center, we require consultation from the pain management service before LMWH is administered to any patient undergoing neuraxial anesthesia. In our experience, such consultation reduces the misuse of this medication in high-risk patients. This type of required consultation would be easier to automate in a system with computerized order entry. For instance, if an anticoagulant was requested on a patient already receiving a typical neuraxial anesthetic, an alert could be displayed notifying the clinician that prior approval from the anticoagulation, pain, or anesthesia service is required, and that pharmacy would not be able to fill the request without such approval.

The most effective intervention might be creating standard procedures, such as implementing a DVT prophylaxis protocol or using brightly colored wristbands to signify previous administration of LMWH. It would be reasonable to create a protocol for patients who receive neuraxial anesthesia that requires the use of mechanical devices for the first 24 hours, followed by the use of pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis. This would ensure adequate time between removal of the needle and initiation of anticoagulation.

In summary, both neuraxial anesthesia and pharmacologic prophylaxis are valuable risk reducing measures. To reduce the risk of complications associated with their simultaneous use, however, hospitals should implement strict guidelines for the use of LMWH with neuraxial anesthesia.

Take-Home Points

- Pharmacologic prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism and neuraxial anesthesia are effective means of reducing postoperative complications.

- Spinal hematoma is a rare complication of neuraxial anesthesia, but the risk is increased in patients treated with LMWHs. Risk can be reduced with adherence to the ASRA guidelines, which call for close attention to dosing and timing of administration.

- Staff education and implementation of automated checks and alerts may reduce the inappropriate use of LMWH in the setting of neuraxial anesthesia.

Tracy Minichiello, MD Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine Director, Anticoagulation Services University of California, San Francisco

References

1. Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:338S-400S.[ go to PubMed ]

2. Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, deFerranti S, et al. The comparative effects of postoperative analgesic therapies on pulmonary outcome: cumulative meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:598-612.[ go to PubMed ]

3. Carli F, Mayo N, Klubien K, Schricker T, Trudel J, Belliveau P. Epidural analgesia enhances functional exercise capacity and health-related quality of life after colonic surgery: results of a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:540-549.[ go to PubMed ]

4. Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM. Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:409-423.[ go to PubMed ]

5. Rigg JR, Jamrozik K, Myles PS, et al. Epidural anaesthesia and analgesia and outcome of major surgery: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1276-1282.[ go to PubMed ]

6. Capdevila X, Barthelet Y, Biboulet P, Ryckwaert Y, Rubenovitch J, d'Athis F. Effects of perioperative analgesic technique on the surgical outcome and duration of rehabilitation after major knee surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:8-15.[ go to PubMed ]

7. Bergqvist D, Wu CL, Neal JM. Anticoagulation and neuraxial regional anesthesia: perspectives. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:163-6.[ go to PubMed ]

8. Vandermeulen EP, Van Aken H, Vermylen J. Anticoagulants and spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:1165-77.[ go to PubMed ]

9. Lumpkin MM. FDA Public Health Advisory [Food and Drug Administration Web site]. December 15, 1997. Available at: [ go to related site ]. Accessed March 2, 2005.

10. Liu SS, Mulroy MF. Neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia in the presence of standard heparin. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23(6 Suppl 2):157-63.[ go to PubMed ]

11. Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Benzon H, et al. Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient: defining the risks (the second ASRA Consensus Conference on Neuraxial Anesthesia and Anticoagulation). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:172-97.[ go to PubMed ]

12. Horlocker TT. Low molecular weight heparin and neuraxial anesthesia. Thromb Res. 2001;101:V141-54.[ go to PubMed ]

Table

Table. Anesthetic Management of Patients Receiving LMWH (11).

| Preoperative LMWH

|

| Postoperative LMWH

|

Figures

Figure 1. Spinal Anatomy and Epidural Placement. (Illustration by Chris Gralapp)

Figure 2. Epidural Hematoma. Arrow indicates large spinal mass at posterior lateral L3-L4 level, associated with severe narrowing of spinal canal. Actual image not from the patient in case presentation.