"Recurrent" Appendicitis

The Case

An 85-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with right lower quadrant pain. On physical examination, the patient showed rebound tenderness with guarding. He received a CT scan of his abdomen, which revealed an inflamed, dilated appendix with surrounding inflammatory changes. The patient was taken to the operating room (OR) for laparoscopic appendectomy. The surgeon had recently joined the medical staff after completing a general surgery residency and then a breast surgery fellowship, and so was still subject to proctoring. The operative report notes that two other surgeons came into the OR to confirm that the appendix was removed with no retained tissue.

Postoperatively, the patient continued to have right lower quadrant pain, which led to a repeat CT scan showing inflammatory changes in the right pericecal region. Because the pathological specimen from the appendectomy had not yet been read, the pathologist was called to determine whether there were some findings that might explain the patient's persistent symptoms. When she examined the specimen, she found no appendiceal tissue.

The patient was emergently taken back to the OR, and the appendix was located and excised. The patient had a stormy postoperative course, complicated by aspiration pneumonia requiring intubation, but ultimately made a full recovery.

The Commentary

This case provides an opportunity to review two important issues in surgery: (i) medical errors associated with the management of acute appendicitis and (ii) issues related to training and operative privileging as the discipline becomes increasingly specialized.

Appendicitis is one of the most common surgical diseases encountered, with approximately 250,000 appendectomies performed annually in the United States.(1) Although appendectomy (either open or laparoscopic) is a relatively safe operation compared with other surgical procedures, appendicitis in the elderly can be a challenging problem, with substantially higher rates of missed and delayed diagnoses, perforation, and postoperative morbidity and mortality. For the general population, the mortality rate following appendectomy is less than 1%; however, in elderly patients, reported mortality rates range from 4% to 8%.(2-4) Similarly, complication rates of 20% to 30% are reported for patients older than 65 compared to 7% to 10% for those younger than 65.(5) The higher rate of complications in the elderly may be due in part to the higher observed rates of perforation (50%–70% in the elderly compared to approximately 20% in the general population).(2,3,6)

The most common medical error encountered in the treatment of appendicitis is a missed or delayed diagnosis, especially in the elderly. In one study, a preoperative diagnosis of appendicitis was made in fewer than half of elderly patients and an incorrect admitting diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of perforation.(3) The most common misdiagnoses were bowel obstruction in patients with perforated appendicitis and diverticulitis in those without perforations. Because both of these conditions are generally treated nonoperatively, such misdiagnoses can be associated with a significant delay in operative intervention and subsequent increased risk of perforation.

Overdiagnosis of appendicitis is also an issue. Although the use of CT scanning has decreased this rate, a recent multi-institutional study suggests that the negative appendectomy rate (i.e., surgery is performed for presumed appendicitis, but the appendix proves to be normal) is still 6%.(7) In such cases, the surgeon traditionally removes the normal-appearing appendix because 20% to 40% will have pathological abnormalities (8) not visible to the surgeon's eye—primarily endoappendicitis or inflammation that is confined to the mucosa or inner wall of the appendix. In addition, if the operation was performed open, future physicians might be confused when a patient sporting a right lower quadrant "appendectomy" incision presents with true appendicitis in the future. However, such a "tell-tale" incision is not found following laparoscopic exploration, and many surgeons will choose to leave a normal-appearing appendix in place. In a study of more than 1500 such patients, only a tiny minority (0.2%) went on to develop clinical appendicitis requiring reoperation.(9) Taken together, this suggests that a normal-appearing appendix seen on laparoscopic evaluation may safely be left in place.

Once in the operating room, there are several technical errors that can occur, primarily accidental injury to adjacent bowel or bleeding (either intraoperative or postoperative). If a laparoscopic approach is used, there is the additional risk of injury during trocar (the port used to access the abdomen) placement to the bowel (which can go unrecognized) or vasculature (which can be particularly harrowing if injury occurs in a major vessel such as the aorta, vena cava, or iliac vessels) and the rare risk of air embolus.

"Recurrent" or "residual" appendicitis can occur when the appendix is not completely removed at the time of the first operation. Most often this is "stump" appendicitis, in which a portion of the distal appendix was removed, but the base of the appendix and some of the proximal appendix were inadvertently left behind. The appendix can vary in size and position relative to the ileocecum, making it challenging to identify the base of the appendix, especially in the setting of acute inflammation. A laparoscopic approach can magnify these issues given the limited visual field, two-dimensional image, and lack of tactile feedback for the surgeon.(10)

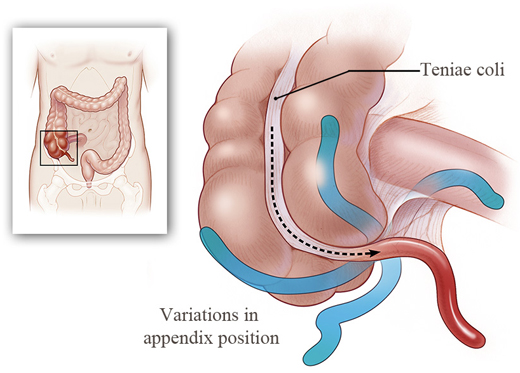

What happened in this case? Case reports have described the appendix being partially retracted into the wall of the cecum, as well as removal of the appendix epiploica (or a large piece of fat attached to the wall of the appendix) instead of the actual appendix.(11) This last scenario could explain the absence of appendiceal tissue on pathologic examination in this case. Epiploica can twist on themselves and necrose due to a lack of blood supply and mimic the appearance of appendicitis on both imaging and exploration. A well-known approach to ensuring identification of the base of the appendix is to follow the teniae coli of the cecum (Figure). These longitudinal strips of muscle consistently have their confluence at the base of the appendix.

This case also brings up some important and timely issues regarding the training and credentialing of general surgeons in light of the increasing specialization of surgery. The average general surgery resident performs 20 laparoscopic appendectomies during his or her general surgery residency, making it one of the 20 most common procedures performed during such residencies.(12) Interestingly, there is some evidence that this correlates exactly with the number of procedures required for competency in "learning curve" analyses.(13,14) Like many procedures, however, the distribution of the experience level is highly skewed and variable, suggesting that a few outliers perform many of these procedures (thereby raising the mean) and many residents perform relatively few of them. It is also important to note that the 20 procedures are performed over a 5-year residency, and it may therefore be several years between when an appendectomy is performed as a resident and when the first one is encountered in practice. This is compounded when a clinical fellowship during which abdominal operations are not performed is completed, such as in this case.

Individual hospitals retain primary responsibility for ensuring the competency of their practicing surgeons through operative privileging. Traditionally, operative privileges have been based on proxies such as completion of residency, board certification (passing a written qualifying and oral certifying exam), case volume, and personal recommendation. Surgeons believe that self-regulation is part of their professional responsibility to the public and that only other surgeons possess the training required to evaluate competence. The American Surgical Association states that privileges must match each surgeon's ongoing practice, be based on practice data, and involve the demonstration of technical proficiency—under local governance.(15) However, it is still unclear exactly how this should be achieved. Proctoring is one approach that has been adopted in which an experienced surgeon supervises the operation as an impartial observer but does not actively participate in the operative procedure.(16) This case suggests that perhaps more active involvement by a preceptor or mentor who can actually double-scrub an operation as a newly minted surgeon is performing his or her first operation might be a more effective approach to ensuring the safety of the patient during the unavoidable learning curve.

A number of policy and cultural changes attempt to address the issue of technical error in surgery. Some, such as increased specialization and prolonged clinical training, have inadvertent negative consequences for core general surgery procedures, such as appendectomy. One approach to decreasing technical errors for emergency general surgery procedures in the era of increased specialization is the development of an "acute care surgery" specialty. Although this may be feasible and lead to improvements at large academic institutions, it is not clear that this is reasonable in all clinical settings. Other interventions such as regionalization or selective referral for complex operations like esophagectomy and pancreatectomy may improve outcomes.(17) However, 73% of technical errors occur with experienced surgeons operating within their field of expertise, and more than 80% were performing routine operations but often under extenuating circumstances, such as complicated patient factors (61%) or systems failures (21%).(18) This suggests that more general interventions are required to decrease technical errors in surgery.

Take-Home Points

This case highlights the following important patient safety issues in the treatment of laparoscopic appendectomy in elderly patients:

- It is critical that the base of the appendix is identified by following the teniae coli (or longitudinal muscles on the wall of the colon) to their confluence.

- Elderly patients are at increased risk of missed and delayed diagnosis of appendicitis, leading to higher rates of perforation. Clinicians must have a high index of suspicion for appendicitis in elderly patients with abdominal pain.

- Elderly patients are at markedly increased risk of morbidity and mortality following appendectomy and must be carefully monitored postoperatively.

- Hospitals and surgical leadership must ensure competency of their operating surgeons through careful assessment prior to granting operative privileges.

- Surgeons must take the lead in developing new methods to measure and improve competency.

Caprice C. Greenberg, MD, MPH Assistant Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School Director, Center for Surgery & Public Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital Faculty, Center for Outcomes & Policy Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

References

1. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910-925. [go to PubMed]

2. Hardin DM Jr. Acute appendicitis: review and update. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2027-2034. [go to PubMed]

3. Storm-Dickerson TL, Horattas MC. What have we learned over the past 20 years about appendicitis in the elderly? Am J Surg. 2003;185:198-201. [go to PubMed]

4. Temple CL, Huchcroft SA, Temple WJ. The natural history of appendicitis in adults. A prospective study. Ann Surg. 1995;221:278-281. [go to PubMed]

5. Guller U, Jain N, Peterson ED, Muhlbaier LH, Eubanks S, Pietrobon R. Laparoscopic appendectomy in the elderly. Surgery. 2004;135:479-488. [go to PubMed]

6. Yamini D, Vargas H, Bongard F, Klein S, Stamos MJ. Perforated appendicitis: is it truly a surgical urgency? Am Surg. 1998;64:970-975. [go to PubMed]

7. Cuschieri J, Florence M, Flum DR, et al. Negative appendectomy and imaging accuracy in the Washington State Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2008;248:557-563. [go to PubMed]

8. Chiarugi M, Buccianti P, Decani L, et al. "What you see is not what you get". A plea to remove a 'normal' appendix during diagnostic laparoscopy. Acta Chir Belg. 2001;101:243-245. [go to PubMed]

9. Kraemer M, Ohmann C, Leppert R, Yang Q. Macroscopic assessment of the appendix at diagnostic laparoscopy is reliable. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:625-633. [go to PubMed]

10. Al-Dabbagh AK, Thomas NB, Haboubi N. Stump appendicitis. A diagnostic dilemma. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:73-74. [go to PubMed]

11. Somerville PG, Lavelle MA. Residual appendicitis following incomplete laparoscopic appendectomy. Br J Surg. 1996;83:869. [go to PubMed]

12. Bell RH Jr., Biester TW, Tabuenca A, et al. Operative experience of residents in US general surgery programs: a gap between expectation and experience. Ann Surg. 2009;249:719-724. [go to PubMed]

13. Katkhouda N, Friedlander MH, Grant SW, et al. Intraabdominal abscess rate after laparoscopic appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2000;180:456-459. [go to PubMed]

14. Park A, Kavic SM, Lee TH, Heniford B. Minimally invasive surgery: the evolution of fellowship. Surgery. 2007;142:505-511. [go to PubMed]

15. Bass BL, Polk HC, Jones RS, et al. Surgical privileging and credentialing: a report of a discussion and study group of the American Surgical Association. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:396-404. [go to PubMed]

16. Satava RM. Proctors, preceptors, and laparoscopic surgery. The role of "proctor" in the surgical credentialing process. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:283-284. [go to PubMed]

17. Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ. Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4671-4678. [go to PubMed]

18. Regenbogen SE, Greenberg CC, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Zinner MJ, Gawande AA. Patterns of technical error among surgical malpractice claims: an analysis of strategies to prevent injury to surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:705-711. [go to PubMed]

Figure

Figure. Graphic depicting various locations of the appendix. A reliable approach to locating the appendix is following the teniae coli.(Illustration © 2010 by Chris Gralapp.)